Complete History of the Palais Garnier

From Second Empire dream to enduring icon — a palace where architecture performs.

Table of Contents

Charles Garnier: Life & Vision

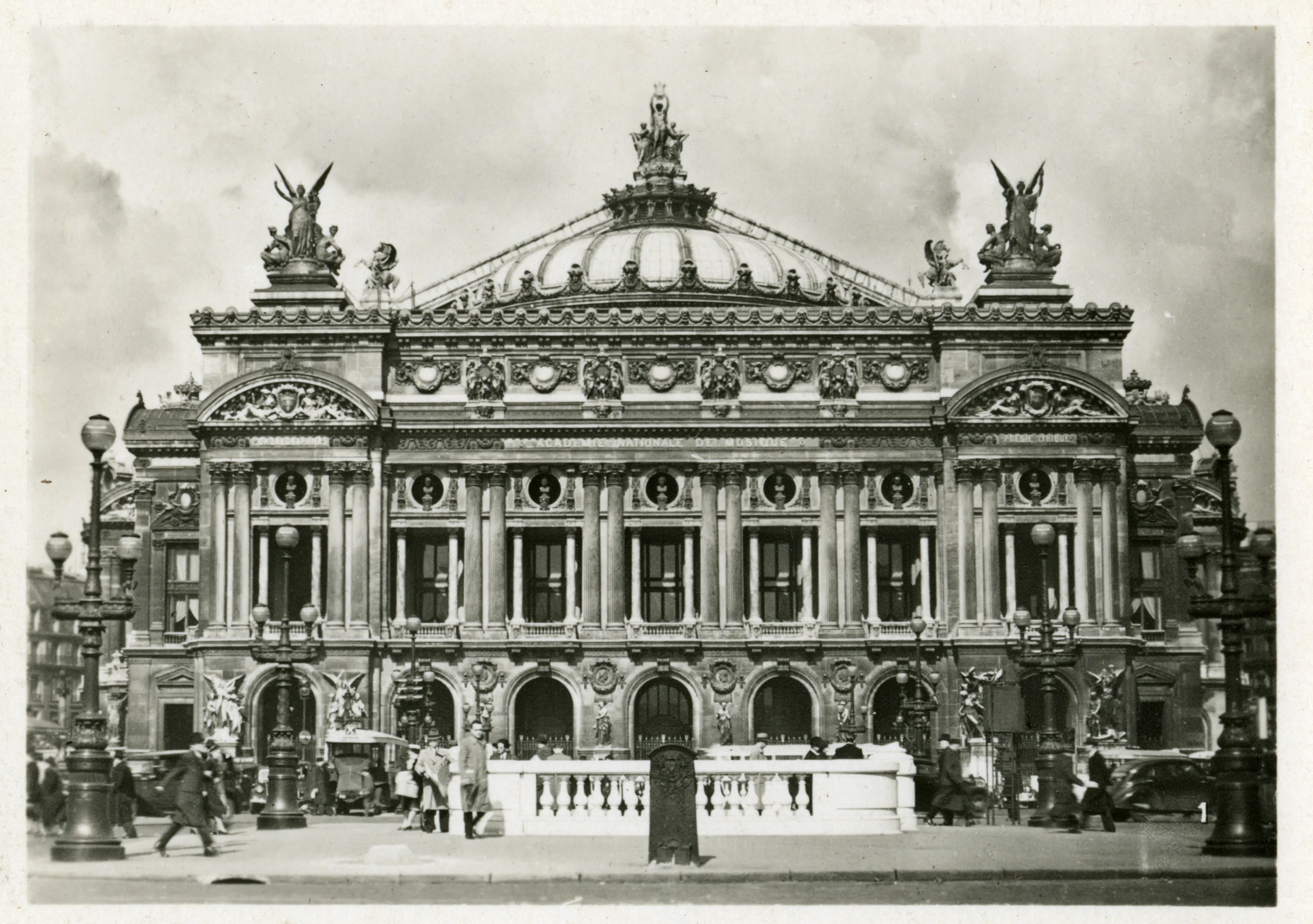

Charles Garnier (1825–1898) emerged from the École des Beaux‑Arts with a talent for synthesis — he could gather Greek clarity, Roman grandeur, Renaissance grace, and Baroque theater into a single, persuasive language. In 1861, barely 35, he won the competition to design a new imperial opera house for a Paris being remade by Baron Haussmann. His project promised more than a venue: it choreographed a public ritual. People would arrive, ascend, and linger as if the building itself were a performance. The story goes that Empress Eugénie, puzzled by the design, asked what ‘style’ it was. Garnier’s answer — ‘in the Napoleon III style’ — was both a joke and a manifesto: a new style for a new city, confident enough to mix past references with modern ambition.

Garnier understood architecture as movement through light. One passes from compressed entry to unfolding space, from shadow to glitter, until the Grand Staircase reveals itself like a stage set awaiting its cast. Under the gilding lies iron and glass — the modern bones that made the fantasy possible. This is Second Empire eclecticism at its most articulate: not a collage of quotations but a seamless score where each motif (marble, onyx, stucco, mosaic) supports the next. The result is not pastiche but performance — a building that mirrors Paris back to itself and invites everyone to play a part in the evening’s grand entrance.

Commission, Site & Construction

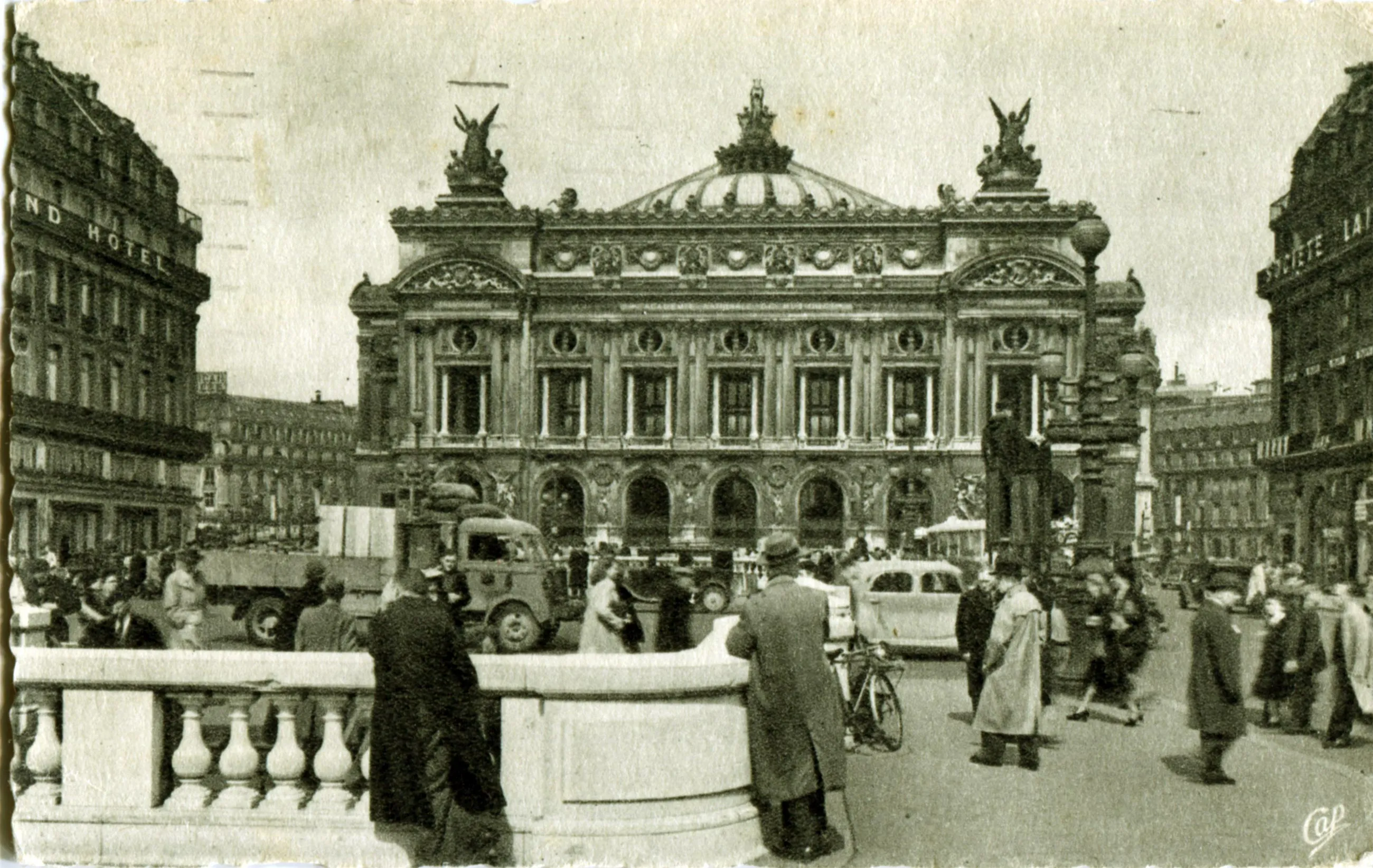

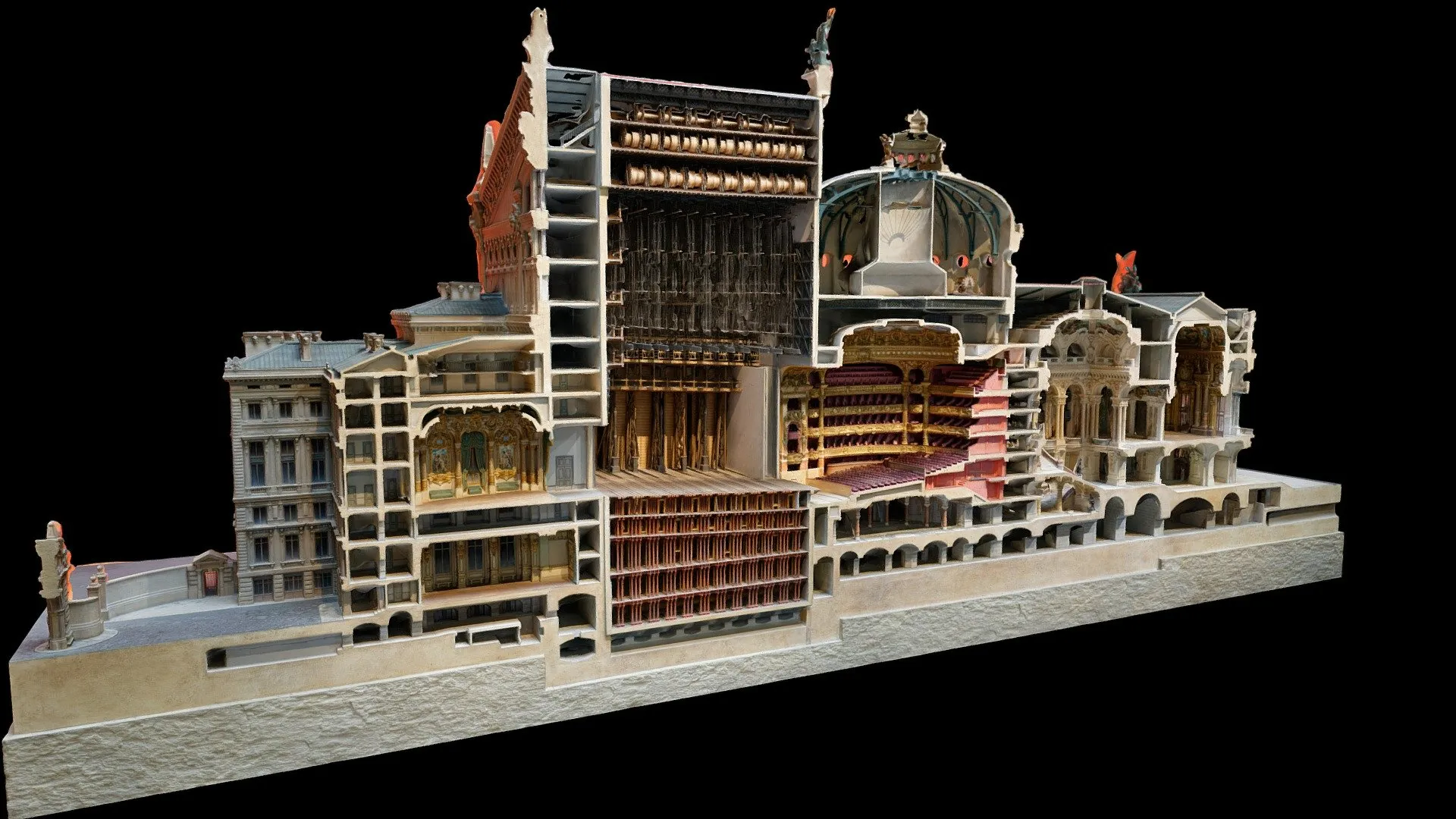

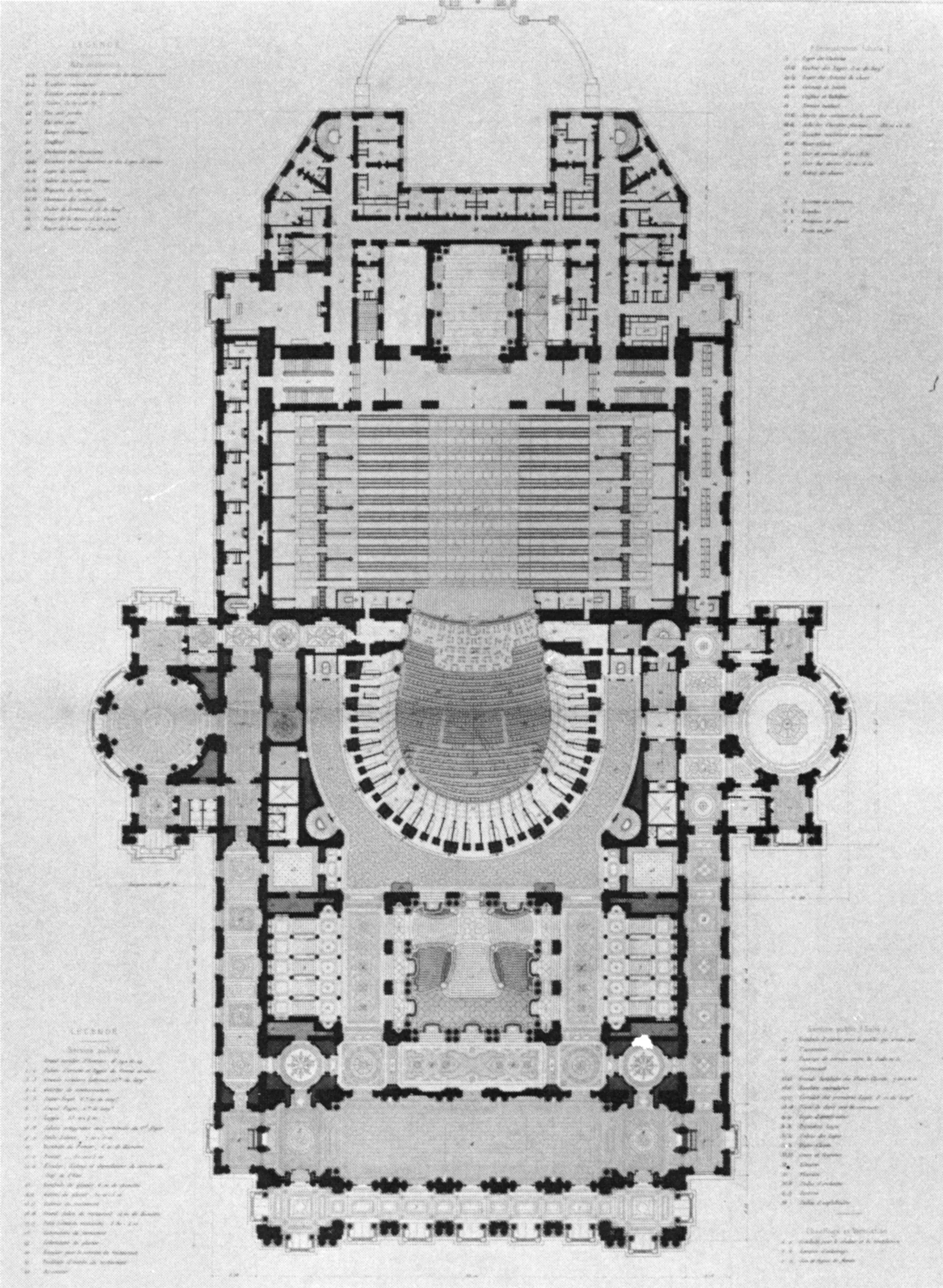

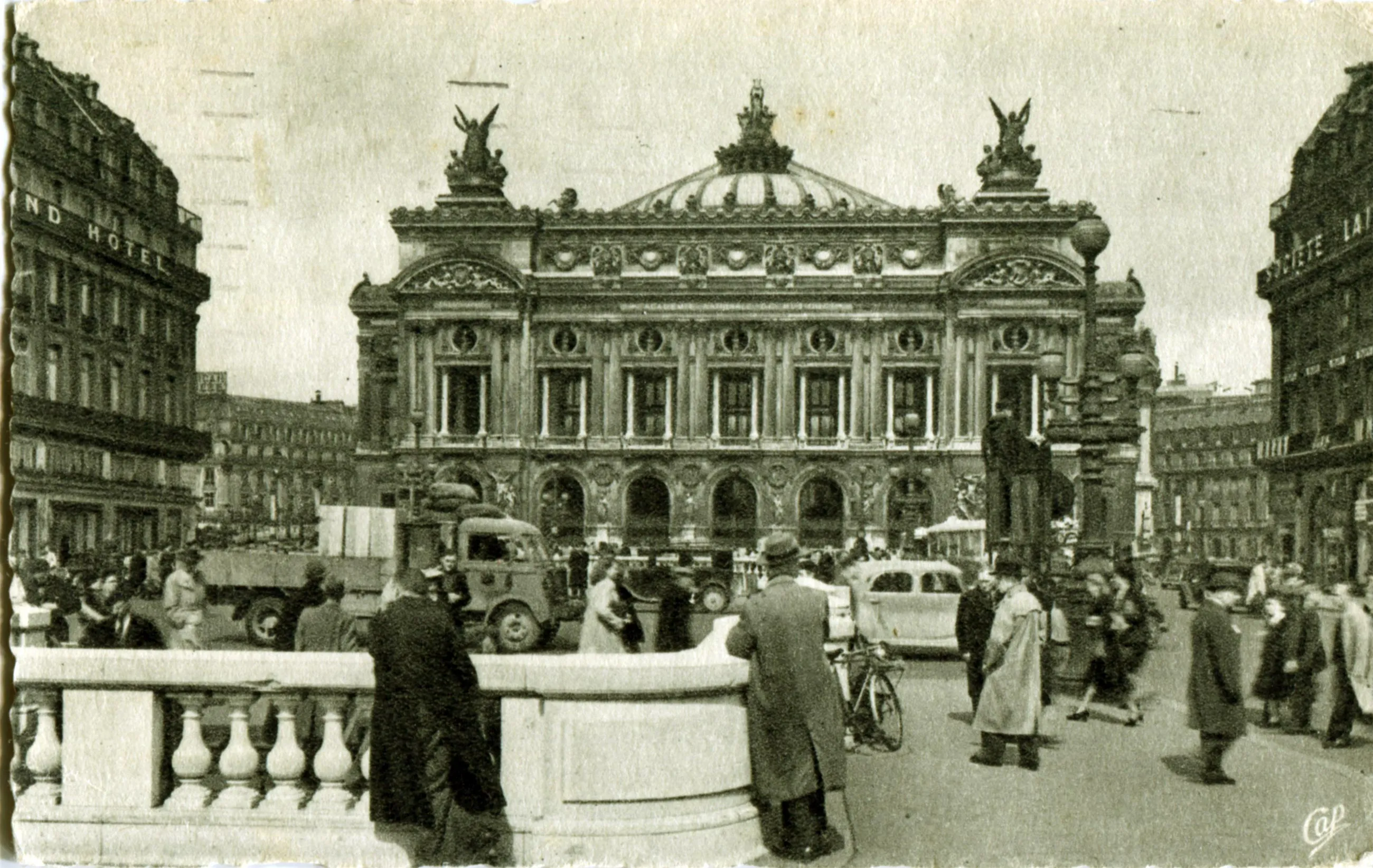

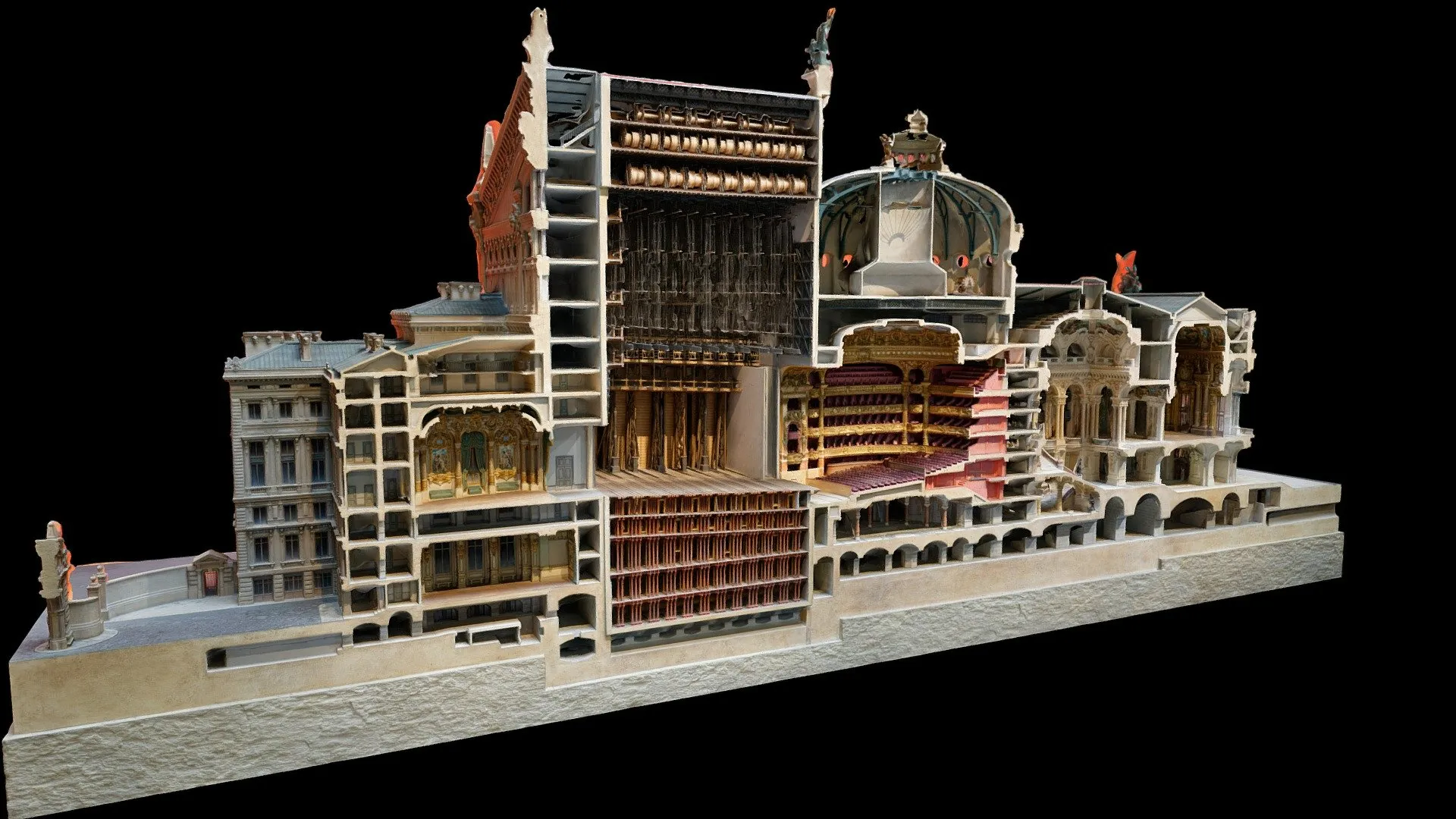

In the 1850s and 60s, Haussmann’s boulevards carved new axes through Paris and demanded worthy monuments. After an assassination attempt near the old opera house, Napoleon III endorsed a new, safer, fire‑resistant theater set as the climax of a straight perspective: Avenue de l’Opéra. Construction began in 1862. The site proved tricky — unstable subsoil and rising groundwater forced engineers to create a vast cistern beneath the stage to stabilize foundations. This functional reservoir, glinting in the half‑dark, later fed the legend of an underground ‘lake’. Aboveground, a forest of scaffolding grew as stonecutters, sculptors, and gilders turned drawings into ornament.

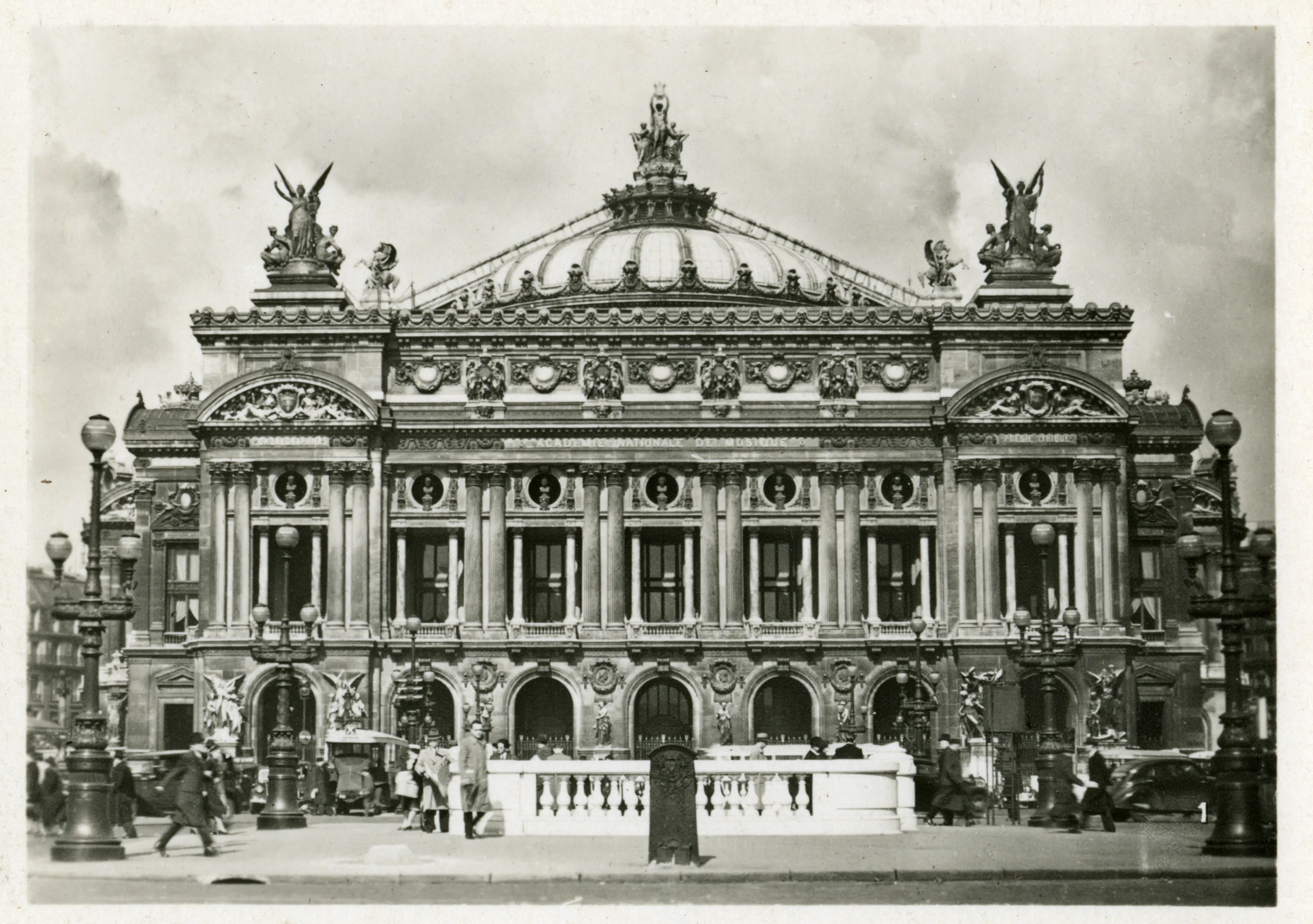

History intervened. The Franco‑Prussian War and the Paris Commune (1870–71) halted work; the half‑finished shell became a witness to upheaval. When calm returned, the project resumed, now under the Third Republic. In 1875, the opera opened with a lavish inauguration. Outside, the façades draped themselves in allegory and marble figures; inside, materials formed a symphony — red and green marbles, Algerian onyx, stuccoes, mosaics, mirrors, and leaf gold applied in breath‑held strokes. Garnier joked that he had invented a style that bore his name. In truth, the building had invented a way of moving through Parisian society, and Paris adopted it with delight.

Procession & Design Language

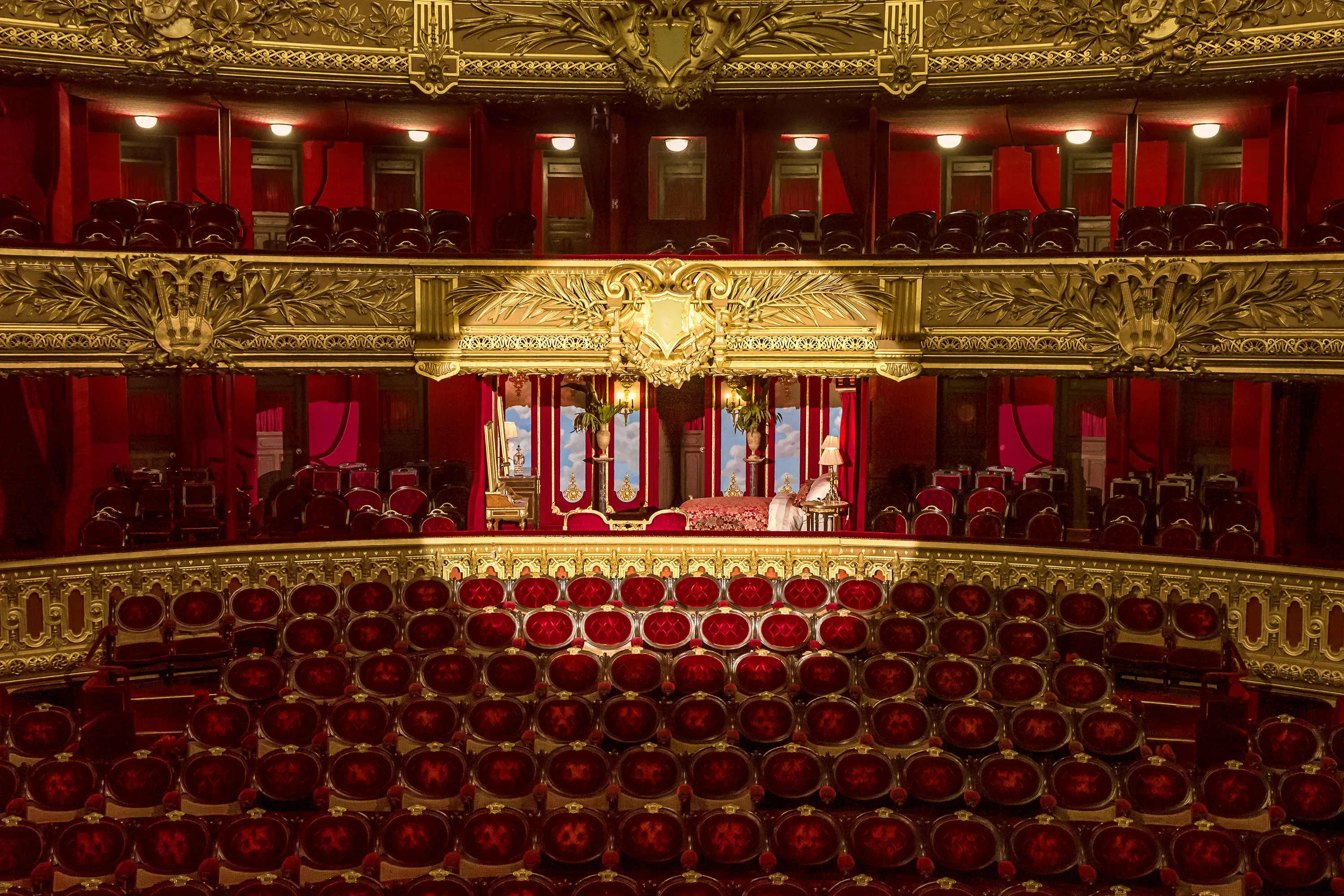

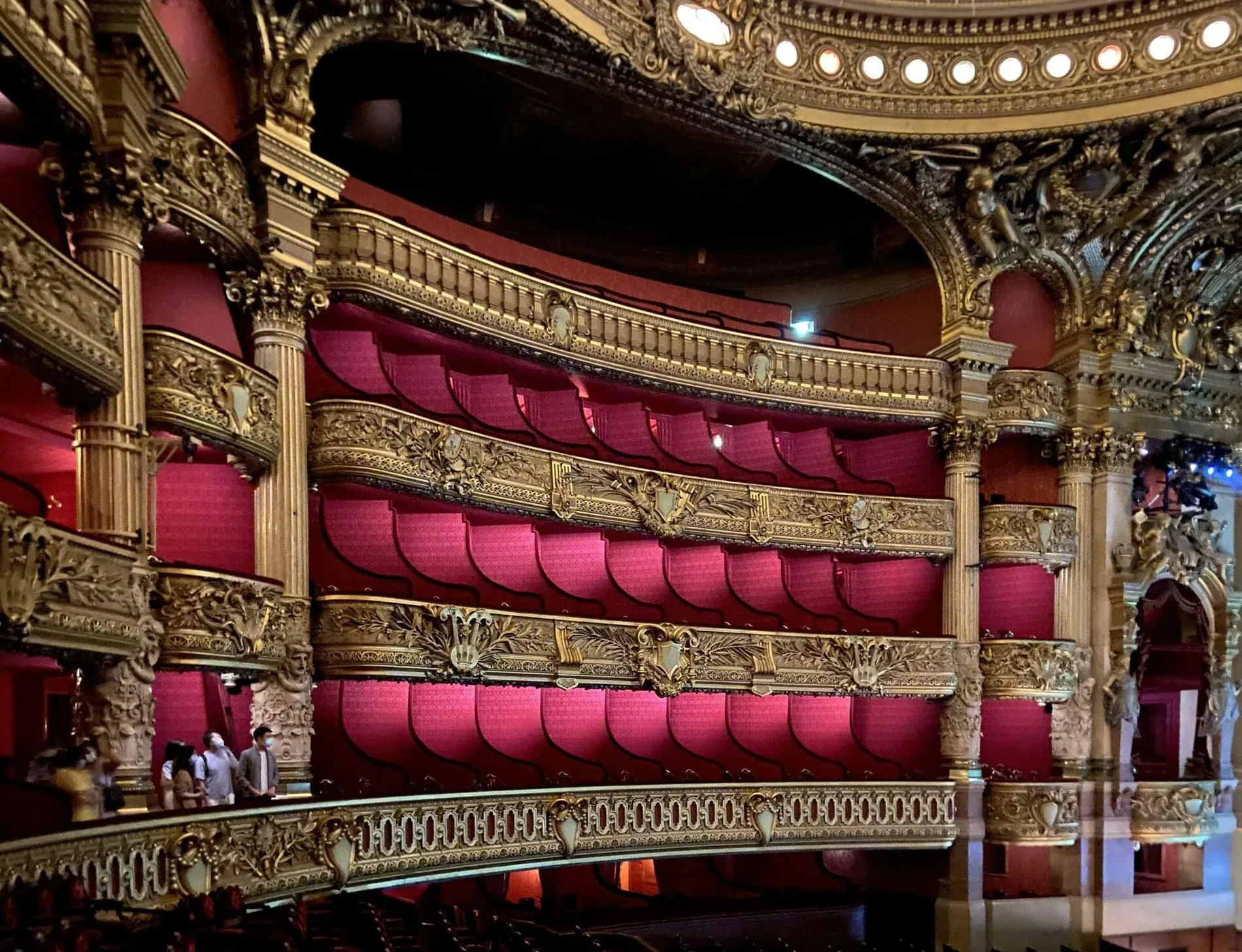

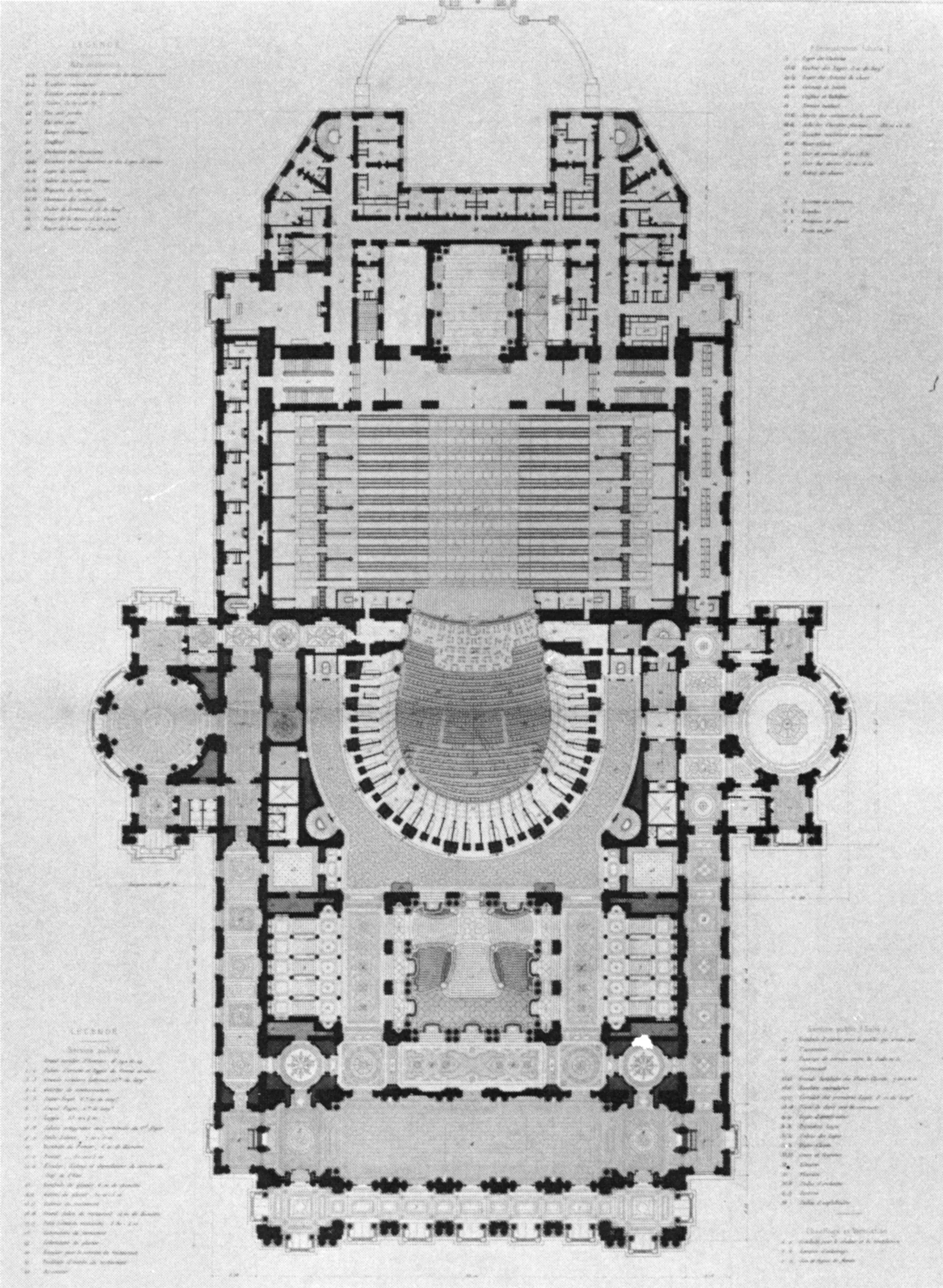

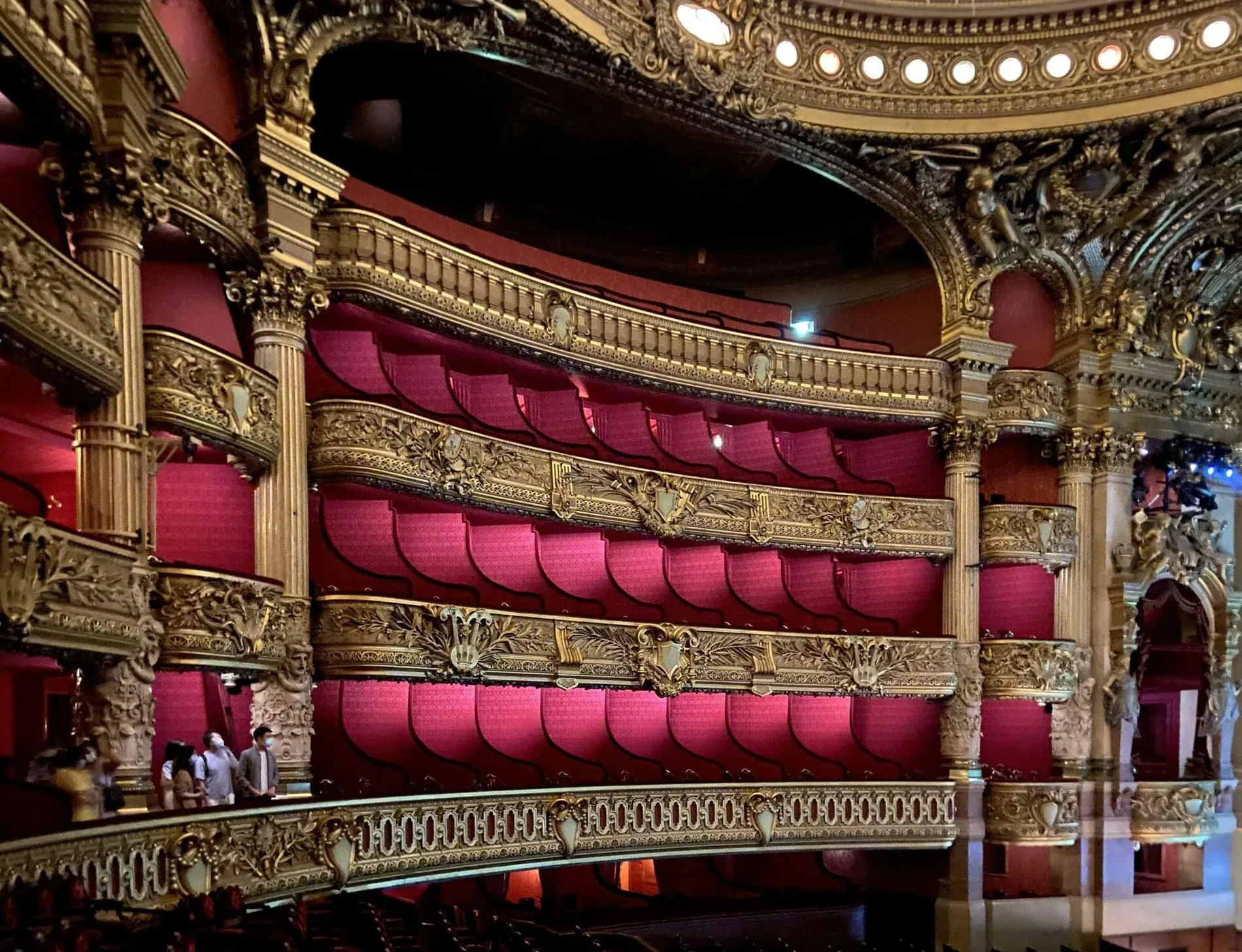

The Palais Garnier unfolds as a procession. One passes through colonnades and rotundas where sculpture presides, then into vestibules that compress the body before releasing it onto the Grand Staircase — that river of marble where landings read like theater boxes. From those balconies, the city once watched itself arrive, dresses rustling, opera cloaks gleaming, gossip perched on the lips like a final aria. Materials heighten the choreography: onyx handrails warmed by hands, veined marbles catching lamplight, bronze candelabra curled with nymphs and masks, and vaults painted with allegories of dance and music.

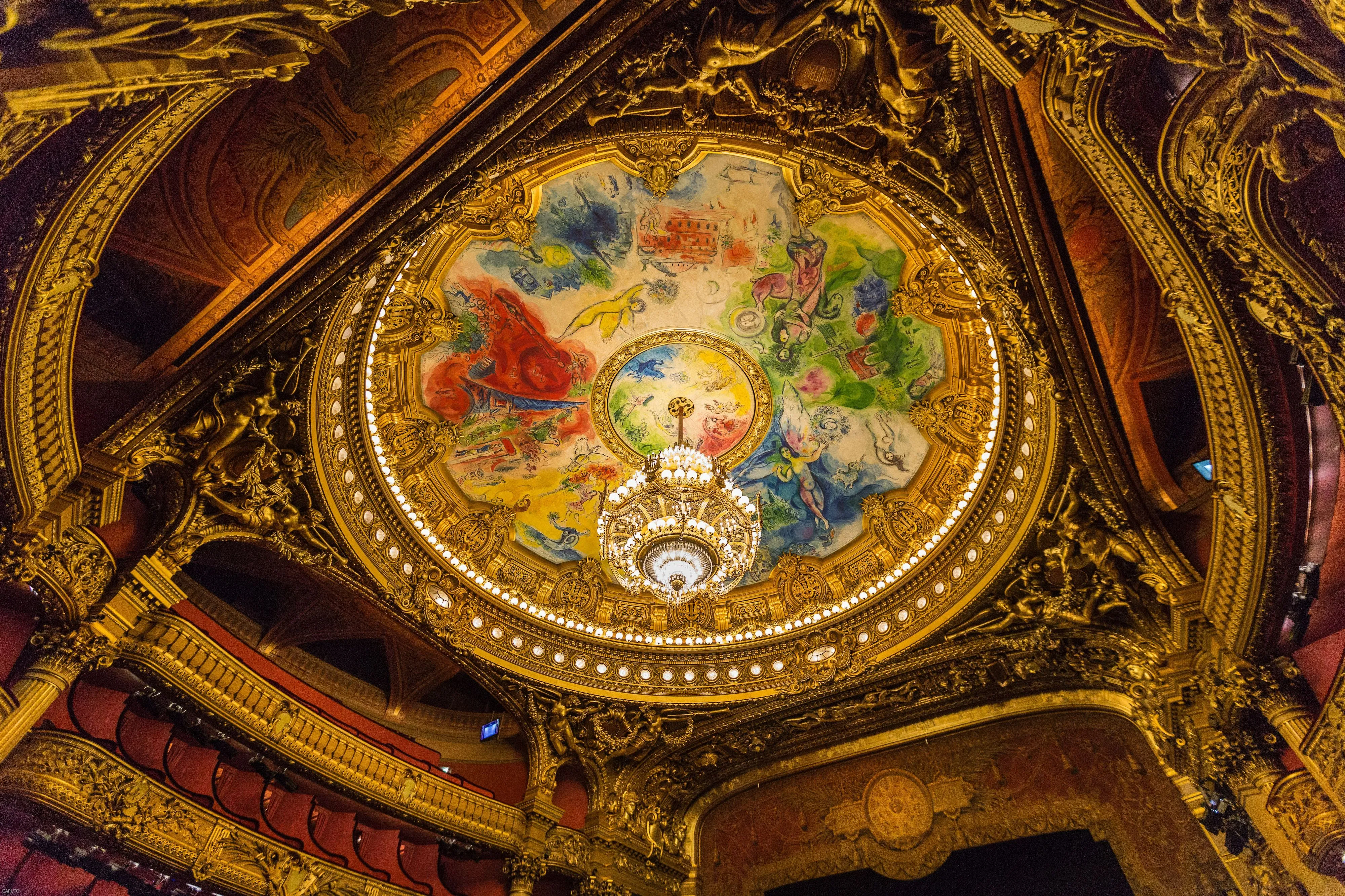

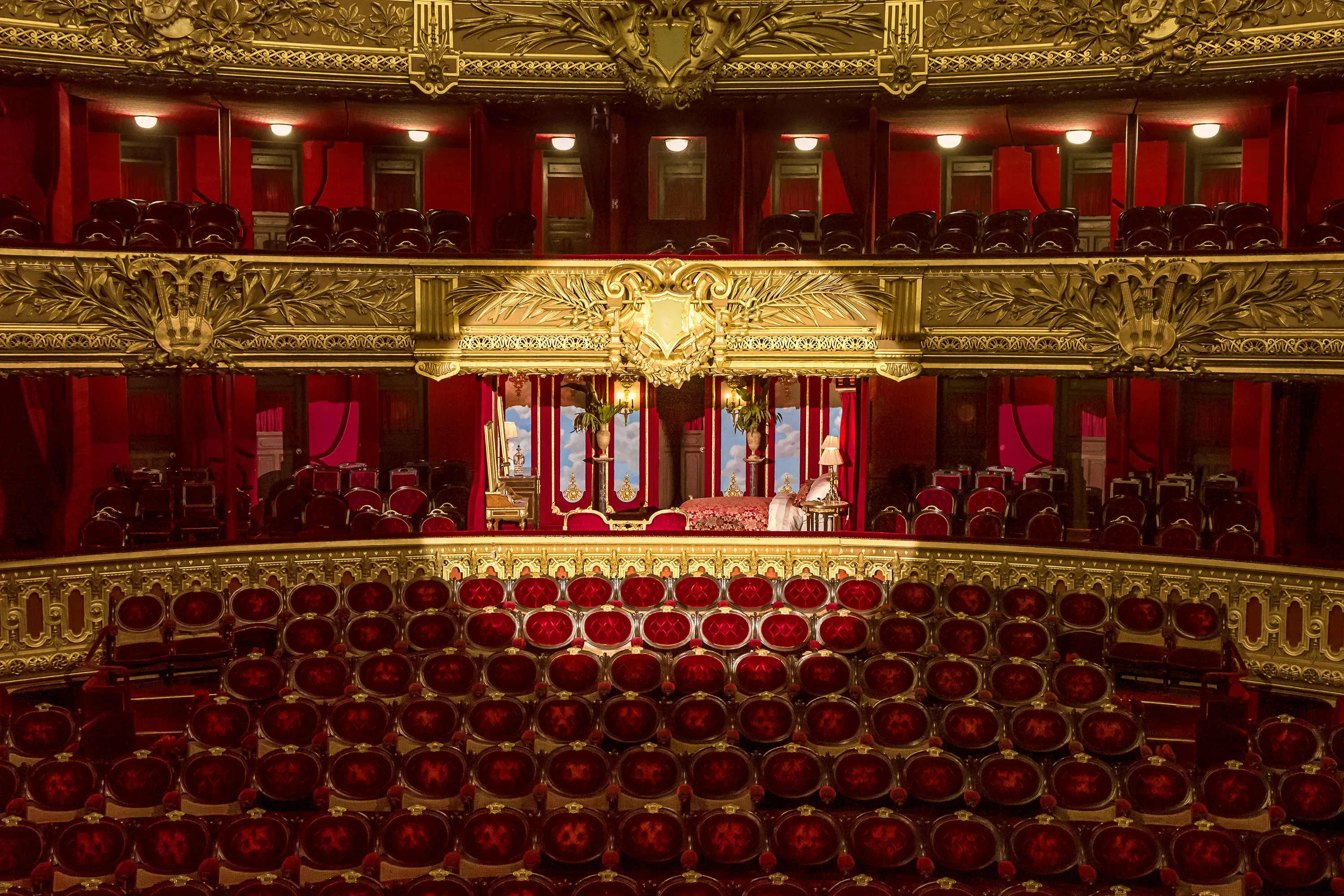

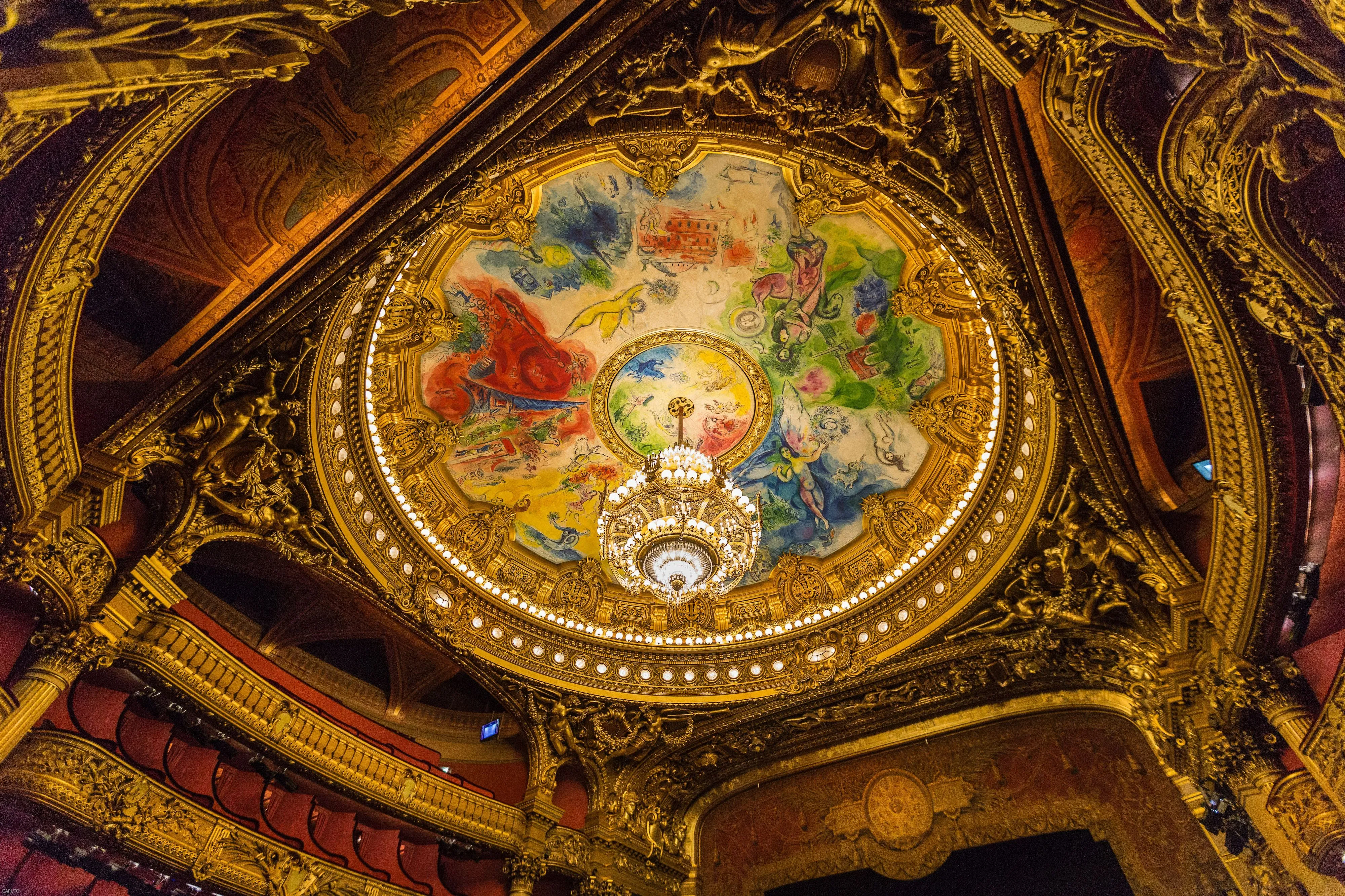

Above, the Grand Foyer stretches in gold and mirror, a Parisian echo of Versailles. Chandeliers multiply into galaxies across polished surfaces; painted ceilings unfurl a festival of arts. Through high windows, the boulevards glide past like a second stage. In 1964, a new overture joined the score: Marc Chagall’s ceiling in the auditorium. Its colors bathe the great chandelier in a modern glow, saints of music and fragments of beloved operas drifting like a dream above the crimson and gold. The palace learned a new note without losing the old refrain.

Masterworks: Staircase, Foyer & Ceiling

At the heart of the visit, the Grand Staircase rises like a marble landscape: steps cascade, landings pause, balustrades swirl. It is a place to linger and to be seen, where architecture becomes social ritual. Alongside, the Grand Foyer extends in a glittering sequence of mirrors and painted vaults, its gilded pilasters and sculpted masks framing views out to the animated boulevards. Every surface is tuned to light, every detail an invitation to slow down and look.

When accessible, the auditorium deepens the encounter. Crimson velvet and gold leaf cradle a great crystal chandelier, while Chagall’s ceiling floats above in luminous color. The room’s horseshoe form recalls European opera traditions; behind its decoration lies subtle acoustics and ingenious stage machinery. Here, a 19th‑century jewel box meets a 20th‑century color poem — a dialogue of eras that keeps the house both rooted and renewed.

Legends: Chandelier, ‘Lake’ & Phantom

Legends cling to the Palais Garnier like perfume. In 1896, a counterweight from the great chandelier fell, igniting rumors that the building was cursed and seeding a century of tales. Below the stage, an underground cistern — created to tame a difficult water table and steady the foundations — became the ‘lake’ of Gaston Leroux’s imagination, where a masked figure slips between pillars. Add creaking ropes, drafty corridors, and the hush of rehearsal, and it is easy to see how superstition took the stage.

Myth and fact mingle gracefully here. The chandelier was repaired and reinforced; safety systems multiplied. The cistern remains a working reservoir, a training ground for firefighters, and a quiet guardian against shifting soils. On the roof, bees busy themselves among hives, making Opéra honey with a view of Paris’s domes. The building keeps its mysteries, but they sit alongside maintenance schedules — and together they make the palace feel alive.

Craft, Materials & Authenticity

Everything at the Palais Garnier is crafted for effect and durability: stuccoes modeled to read as carved stone, mosaics set with shimmering tesserae that catch lamplight, and leaf gold laid in whisper‑thin sheets that warm the eye. Marbles came from France and Italy; onyx from Algeria; iron frames and trusses hide under stone to carry loads with modern confidence. Stage machinery, once powered by teams and counterweights, evolved through gaslight to electricity while preserving the room’s ritual glow.

Conservators balance renewal with restraint. Gilding must be cleaned without erasing its hand; stucco repaired without smoothing away tool marks; marble stabilized where seams have loosened with age. The goal is not to make the palace look new, but to keep its theatrics legible — to let time and care sit together so the building can keep performing for another century.

Visitors, Education & Changing Displays

Daytime visits open the house to architecture lovers, students, and families who want to see how spectacle is built. Audio guides trace symbols and stories through corridors; guided tours connect anecdotes to places — the Rotonde des Abonnés where subscribers gathered, the museum‑library where memory is kept, the foyers where light behaves like an instrument.

Displays shift with research and restoration. Models show how scenery flies in and out; costumes reveal the hand of workshops; drawings and photographs bring back vanished décors. The opera’s magic rests on craft — carpenters, painters, gilders, machinists — and the visit route increasingly makes that invisible labor visible.

Fire, Wars & Repairs

Like every great theater, the Palais Garnier has faced danger — war, wear, and the constant specter of fire in a building full of wood, fabric, and paint. Behind the scenes, safety systems, fire doors, and modern monitoring work with old‑school vigilance to protect both stage machinery and historic finishes.

The 20th century layered repair upon invention: after periods of wear and smoke, ceilings were cleaned, wiring renewed, and the auditorium crowned with Chagall’s luminous canvas. Each intervention sought a balance — honoring Garnier’s spirit while meeting contemporary standards — so that the palace could remain not a relic, but a living house.

Palais in Popular Culture

The Palais Garnier is a star in its own right: silent films set staircases aflutter; fashion houses borrow its mirrors and light; album covers quote its masks and chandeliers. Few interiors communicate ‘Paris’ so instantly or so generously.

Gaston Leroux’s Phantom escaped the page to haunt stages and screens worldwide, turning the opera’s silhouette into a logo for romance, secrecy, and revelation. Arriving here feels uncannily familiar — like stepping into a dream you’ve already dreamt.

Visiting Today

A visit moves at the building’s tempo: vestibule, rotunda, stair, foyer — a sequence that both elevates and calms. When the auditorium is open, even a brief look floods the senses with red, gold, and the cool blues and greens of Chagall. Elsewhere, high windows frame the boulevards as if they were a moving frieze; mirrors double the chandeliers into constellations. Benches invite unhurried pauses under painted skies.

Practical improvements sit discreetly behind the scenes: step‑free routes, conservation lighting with softer glare, and vigilant safety systems. The result honors Garnier’s intention — to make architecture itself perform — while ensuring today’s visitors can enjoy the show comfortably and safely.

Conservation & Future Plans

Gilding dulls; stucco cracks; marble joints breathe with the seasons; chandeliers ask for constant care. Conservation is a patient art: clean without erasing, strengthen without stiffening, refresh without replacing what gives age its eloquence. Every project is a dialogue with the past and a promise to the future.

Future plans continue this rhythm — expanding research access, refining visitor circulation, upgrading systems that no one should notice, and scheduling restorations in phases so the house can keep welcoming guests. The aim is simple: let the palace age beautifully.

Nearby Paris Landmarks

Steps away rise the grands magasins — Galeries Lafayette and Printemps — whose rooftops offer superb views over zinc roofs and domes. Place Vendôme glitters to the south; the Tuileries and the Louvre are an elegant walk along grand axes. To the north, Saint‑Lazare’s bustle threads modern Paris into the 19th century cityscape.

After your visit, claim a café table and watch the boulevards perform: window displays, umbrellas, the soft theatre of rush hour. It’s the Paris of promenades and golden light — a fitting encore to the palace’s show.

Cultural & National Significance

The Palais Garnier is more than a theater; it is a lesson in how a city imagines itself. It concentrates craftsmanship — carving, casting, painting, sewing, wiring — into a single, legible promise: that beauty is a public good worth sharing. In a city of façades, it invites you inside the façade.

As an architectural destination, it renews the civic pleasure of looking together. Here, spectacle is not only on stage but in the shared act of arrival. The promise endures: to make ordinary time feel a little like opening night, and to remind Paris how well light and marble suit it.

Table of Contents

Charles Garnier: Life & Vision

Charles Garnier (1825–1898) emerged from the École des Beaux‑Arts with a talent for synthesis — he could gather Greek clarity, Roman grandeur, Renaissance grace, and Baroque theater into a single, persuasive language. In 1861, barely 35, he won the competition to design a new imperial opera house for a Paris being remade by Baron Haussmann. His project promised more than a venue: it choreographed a public ritual. People would arrive, ascend, and linger as if the building itself were a performance. The story goes that Empress Eugénie, puzzled by the design, asked what ‘style’ it was. Garnier’s answer — ‘in the Napoleon III style’ — was both a joke and a manifesto: a new style for a new city, confident enough to mix past references with modern ambition.

Garnier understood architecture as movement through light. One passes from compressed entry to unfolding space, from shadow to glitter, until the Grand Staircase reveals itself like a stage set awaiting its cast. Under the gilding lies iron and glass — the modern bones that made the fantasy possible. This is Second Empire eclecticism at its most articulate: not a collage of quotations but a seamless score where each motif (marble, onyx, stucco, mosaic) supports the next. The result is not pastiche but performance — a building that mirrors Paris back to itself and invites everyone to play a part in the evening’s grand entrance.

Commission, Site & Construction

In the 1850s and 60s, Haussmann’s boulevards carved new axes through Paris and demanded worthy monuments. After an assassination attempt near the old opera house, Napoleon III endorsed a new, safer, fire‑resistant theater set as the climax of a straight perspective: Avenue de l’Opéra. Construction began in 1862. The site proved tricky — unstable subsoil and rising groundwater forced engineers to create a vast cistern beneath the stage to stabilize foundations. This functional reservoir, glinting in the half‑dark, later fed the legend of an underground ‘lake’. Aboveground, a forest of scaffolding grew as stonecutters, sculptors, and gilders turned drawings into ornament.

History intervened. The Franco‑Prussian War and the Paris Commune (1870–71) halted work; the half‑finished shell became a witness to upheaval. When calm returned, the project resumed, now under the Third Republic. In 1875, the opera opened with a lavish inauguration. Outside, the façades draped themselves in allegory and marble figures; inside, materials formed a symphony — red and green marbles, Algerian onyx, stuccoes, mosaics, mirrors, and leaf gold applied in breath‑held strokes. Garnier joked that he had invented a style that bore his name. In truth, the building had invented a way of moving through Parisian society, and Paris adopted it with delight.

Procession & Design Language

The Palais Garnier unfolds as a procession. One passes through colonnades and rotundas where sculpture presides, then into vestibules that compress the body before releasing it onto the Grand Staircase — that river of marble where landings read like theater boxes. From those balconies, the city once watched itself arrive, dresses rustling, opera cloaks gleaming, gossip perched on the lips like a final aria. Materials heighten the choreography: onyx handrails warmed by hands, veined marbles catching lamplight, bronze candelabra curled with nymphs and masks, and vaults painted with allegories of dance and music.

Above, the Grand Foyer stretches in gold and mirror, a Parisian echo of Versailles. Chandeliers multiply into galaxies across polished surfaces; painted ceilings unfurl a festival of arts. Through high windows, the boulevards glide past like a second stage. In 1964, a new overture joined the score: Marc Chagall’s ceiling in the auditorium. Its colors bathe the great chandelier in a modern glow, saints of music and fragments of beloved operas drifting like a dream above the crimson and gold. The palace learned a new note without losing the old refrain.

Masterworks: Staircase, Foyer & Ceiling

At the heart of the visit, the Grand Staircase rises like a marble landscape: steps cascade, landings pause, balustrades swirl. It is a place to linger and to be seen, where architecture becomes social ritual. Alongside, the Grand Foyer extends in a glittering sequence of mirrors and painted vaults, its gilded pilasters and sculpted masks framing views out to the animated boulevards. Every surface is tuned to light, every detail an invitation to slow down and look.

When accessible, the auditorium deepens the encounter. Crimson velvet and gold leaf cradle a great crystal chandelier, while Chagall’s ceiling floats above in luminous color. The room’s horseshoe form recalls European opera traditions; behind its decoration lies subtle acoustics and ingenious stage machinery. Here, a 19th‑century jewel box meets a 20th‑century color poem — a dialogue of eras that keeps the house both rooted and renewed.

Legends: Chandelier, ‘Lake’ & Phantom

Legends cling to the Palais Garnier like perfume. In 1896, a counterweight from the great chandelier fell, igniting rumors that the building was cursed and seeding a century of tales. Below the stage, an underground cistern — created to tame a difficult water table and steady the foundations — became the ‘lake’ of Gaston Leroux’s imagination, where a masked figure slips between pillars. Add creaking ropes, drafty corridors, and the hush of rehearsal, and it is easy to see how superstition took the stage.

Myth and fact mingle gracefully here. The chandelier was repaired and reinforced; safety systems multiplied. The cistern remains a working reservoir, a training ground for firefighters, and a quiet guardian against shifting soils. On the roof, bees busy themselves among hives, making Opéra honey with a view of Paris’s domes. The building keeps its mysteries, but they sit alongside maintenance schedules — and together they make the palace feel alive.

Craft, Materials & Authenticity

Everything at the Palais Garnier is crafted for effect and durability: stuccoes modeled to read as carved stone, mosaics set with shimmering tesserae that catch lamplight, and leaf gold laid in whisper‑thin sheets that warm the eye. Marbles came from France and Italy; onyx from Algeria; iron frames and trusses hide under stone to carry loads with modern confidence. Stage machinery, once powered by teams and counterweights, evolved through gaslight to electricity while preserving the room’s ritual glow.

Conservators balance renewal with restraint. Gilding must be cleaned without erasing its hand; stucco repaired without smoothing away tool marks; marble stabilized where seams have loosened with age. The goal is not to make the palace look new, but to keep its theatrics legible — to let time and care sit together so the building can keep performing for another century.

Visitors, Education & Changing Displays

Daytime visits open the house to architecture lovers, students, and families who want to see how spectacle is built. Audio guides trace symbols and stories through corridors; guided tours connect anecdotes to places — the Rotonde des Abonnés where subscribers gathered, the museum‑library where memory is kept, the foyers where light behaves like an instrument.

Displays shift with research and restoration. Models show how scenery flies in and out; costumes reveal the hand of workshops; drawings and photographs bring back vanished décors. The opera’s magic rests on craft — carpenters, painters, gilders, machinists — and the visit route increasingly makes that invisible labor visible.

Fire, Wars & Repairs

Like every great theater, the Palais Garnier has faced danger — war, wear, and the constant specter of fire in a building full of wood, fabric, and paint. Behind the scenes, safety systems, fire doors, and modern monitoring work with old‑school vigilance to protect both stage machinery and historic finishes.

The 20th century layered repair upon invention: after periods of wear and smoke, ceilings were cleaned, wiring renewed, and the auditorium crowned with Chagall’s luminous canvas. Each intervention sought a balance — honoring Garnier’s spirit while meeting contemporary standards — so that the palace could remain not a relic, but a living house.

Palais in Popular Culture

The Palais Garnier is a star in its own right: silent films set staircases aflutter; fashion houses borrow its mirrors and light; album covers quote its masks and chandeliers. Few interiors communicate ‘Paris’ so instantly or so generously.

Gaston Leroux’s Phantom escaped the page to haunt stages and screens worldwide, turning the opera’s silhouette into a logo for romance, secrecy, and revelation. Arriving here feels uncannily familiar — like stepping into a dream you’ve already dreamt.

Visiting Today

A visit moves at the building’s tempo: vestibule, rotunda, stair, foyer — a sequence that both elevates and calms. When the auditorium is open, even a brief look floods the senses with red, gold, and the cool blues and greens of Chagall. Elsewhere, high windows frame the boulevards as if they were a moving frieze; mirrors double the chandeliers into constellations. Benches invite unhurried pauses under painted skies.

Practical improvements sit discreetly behind the scenes: step‑free routes, conservation lighting with softer glare, and vigilant safety systems. The result honors Garnier’s intention — to make architecture itself perform — while ensuring today’s visitors can enjoy the show comfortably and safely.

Conservation & Future Plans

Gilding dulls; stucco cracks; marble joints breathe with the seasons; chandeliers ask for constant care. Conservation is a patient art: clean without erasing, strengthen without stiffening, refresh without replacing what gives age its eloquence. Every project is a dialogue with the past and a promise to the future.

Future plans continue this rhythm — expanding research access, refining visitor circulation, upgrading systems that no one should notice, and scheduling restorations in phases so the house can keep welcoming guests. The aim is simple: let the palace age beautifully.

Nearby Paris Landmarks

Steps away rise the grands magasins — Galeries Lafayette and Printemps — whose rooftops offer superb views over zinc roofs and domes. Place Vendôme glitters to the south; the Tuileries and the Louvre are an elegant walk along grand axes. To the north, Saint‑Lazare’s bustle threads modern Paris into the 19th century cityscape.

After your visit, claim a café table and watch the boulevards perform: window displays, umbrellas, the soft theatre of rush hour. It’s the Paris of promenades and golden light — a fitting encore to the palace’s show.

Cultural & National Significance

The Palais Garnier is more than a theater; it is a lesson in how a city imagines itself. It concentrates craftsmanship — carving, casting, painting, sewing, wiring — into a single, legible promise: that beauty is a public good worth sharing. In a city of façades, it invites you inside the façade.

As an architectural destination, it renews the civic pleasure of looking together. Here, spectacle is not only on stage but in the shared act of arrival. The promise endures: to make ordinary time feel a little like opening night, and to remind Paris how well light and marble suit it.